Who were the lawyers in the Scopes Trial?

- Rev. Walter C. ...

- Dr. Shailer Matthews, Dean of the Divinity School of the University of Chicago

- Dr. Fay Cooper Cole, professor of anthropology, University of Chicago

- Dr. Kirtley F. ...

- Dr. Winterton C. ...

- Dr. Herman Rosenwasser, rabbi linguist from San Francisco

- Dr. H.E. ...

- Dr. Maynard M. ...

- Wilbur A. Nelson, state geologist of Tennessee

- Dr. ...

Who defended John Scopes in his trial?

He was arrested on May 7, 1925, and charged with teaching the theory of evolution. Clarence Darrow, an exceptionally competent, experienced, and nationally renowned criminal defense attorney led the defense along with ACLU General Counsel, Arthur Garfield Hays.

Who was involved in the Scopes Trial?

The prosecution was led by William Jennings Bryan, a former Secretary of State, presidential candidate, and the most famous fundamentalist Christian spokesperson in the country. His strategy was quite simple: to prove John Scopes guilty of violating Tennessee law.

What happened in the Scopes Trial?

Scopes Trial, also called the ‘Monkey Trial,’ highly publicized trial that took place July 10–21, 1925, during which a Dayton, Tennessee, high-school teacher, John T. Scopes, was charged with violating state law by teaching Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution.

Who was the lawyer who prosecuted Scopes?

The prosecution was led by William Jennings Bryan, a former Secretary of State, presidential candidate, and the most famous fundamentalist Christian spokesperson in the country. His strategy was quite simple: to prove John Scopes guilty of violating Tennessee law.

Who was William Jennings Bryan and what role did he play in this trial?

Bryan helped prosecute Tennessee teacher in Scopes trial for teaching evolution. Bryan's greatest concern was the public's increasing acceptance of Darwinian thought and theories of evolution; he pleaded with state legislatures to pass laws barring public schools from teaching evolution.

Why did William Jennings Bryan lose?

His campaign focused on silver, an issue that failed to appeal to the urban voter, and he was defeated in what is generally seen as a realigning election. The coalition of wealthy, middle-class and urban voters that defeated Bryan kept the Republicans in power for most of the time until 1932.

Was Jennings Bryan a defense attorney?

Darrow was almost as famous as Bryan, a defense attorney who had, the previous year, successfully kept the self-confessed killers Leopold and Loeb off death row, arguing that they were mentally incapacitated and too young to be executed.

Who was the attorney for Scopes?

Wells replied that he had no legal training in Britain, let alone in America, and declined the offer. John R. Neal, a law school professor from Knoxville, announced that he would act as Scopes' attorney whether Scopes liked it or not, and he became the nominal head of the defense team.

How long did it take for Scopes to be found guilty?

His teachings, and His teachings alone, can solve the problems that vex the heart and perplex the world. After eight days of trial, it took the jury only nine minutes to deliberate. Scopes was found guilty on July 21 and ordered by Raulston to pay a $100 fine (equivalent to $1,500 in 2020).

How long did the confrontation between Bryan and Darrow last?

The confrontation between Bryan and Darrow lasted approximately two hours on the afternoon of the seventh day of the trial. It is likely that it would have continued the following morning but for Judge Raulston's announcement that he considered the whole examination irrelevant to the case and his decision that it should be "expunged" from the record. Thus Bryan was denied the chance to cross-examine the defense lawyers in return, although after the trial Bryan would distribute nine questions to the press to bring out Darrow's "religious attitude". The questions and Darrow's short answers were published in newspapers the day after the trial ended, with The New York Times characterizing Darrow as answering Bryan's questions "with his agnostic's creed, 'I don't know,' except where he could deny them with his belief in natural, immutable law".

How much was Scopes fined?

Scopes was found guilty and fined $100 (equivalent to $1,500 in 2020), but the verdict was overturned on a technicality. The trial served its purpose of drawing intense national publicity, as national reporters flocked to Dayton to cover the big-name lawyers who had agreed to represent each side.

What was the Scopes v. State case?

John Thomas Scopes and commonly referred to as the Scopes Monkey Trial, was an American legal case in July 1925 in which a high school teacher, John T. Scopes, was accused of violating Tennessee 's Butler Act, which had made it unlawful to teach human evolution in ...

Why did the ACLU oppose the Butler Act?

The ACLU had originally intended to oppose the Butler Act on the grounds that it violated the teacher's individual rights and academic freedom , and was therefore unconstitutional. Principally because of Clarence Darrow, this strategy changed as the trial progressed. The earliest argument proposed by the defense once the trial had begun was that there was actually no conflict between evolution and the creation account in the Bible; later, this viewpoint would be called theistic evolution. In support of this claim, they brought in eight experts on evolution. But other than Dr. Maynard Metcalf, a zoologist from Johns Hopkins University, the judge would not allow these experts to testify in person. Instead, they were allowed to submit written statements so their evidence could be used at the appeal. In response to this decision, Darrow made a sarcastic comment to Judge Raulston (as he often did throughout the trial) on how he had been agreeable only on the prosecution's suggestions. Darrow apologized the next day, keeping himself from being found in contempt of court.

When was the Rhea County Courthouse restored?

The Rhea County Courthouse is a National Historic Landmark. In a $1 million restoration of the Rhea County Courthouse in Dayton, completed in 1979, the second-floor courtroom was restored to its appearance during the Scopes trial.

What was the purpose of the Scopes Trial?

The trial’s proceedings helped to bring the scientific evidence for evolution into the public sphere while also stoking a national debate over the veracity of evolution that continues to the present day. Scopes Trial.

How much was Scopes fined?

With Raulston limiting the trial to the single question of whether Scopes had taught evolution, which he admittedly had, Scopes was convicted and fined $100 on July 21.

What was the climax of the trial?

The trial’s climax came on July 20, when Darrow called on Bryan to testify as an expert witness for the prosecution on the Bible. Raulston moved the trial to the courthouse lawn, citing the swell of spectators and stifling heat inside.

Who led the Butler case?

William Jennings Bryan led for the prosecution and Clarence Darrow for the defense. Jury selection began on July 10, and opening statements, which included Darrow’s impassioned speech about the constitutionality of the Butler law and his claim that the law violated freedom of religion, began on July 13. Judge John Raulston ruled out any test of the ...

Who ruled out the validity of evolutionary theory?

Judge John Raulston ruled out any test of the law’s constitutionality or argument on the validity of evolutionary theory on the basis that Scopes, rather than the Butler law, was on trial. Raulston determined that expert testimony from scientists would be inadmissible.

What was the scopes trial?

On July 21, Scopes was found guilty and fined $100, but the fine was revoked a year later during the appeal to the Tennessee Supreme Court. As the first trial was broadcast live on radio in the United States, the Scopes trial brought widespread attention to the controversy over creationism versus evolution .

When did Darrow ask the jury to find Scopes guilty?

Verdict. On the morning of Tuesday, July 21, Darrow asked to address the jury before they left to deliberate. Fearing that a not guilty verdict would rob his team of the chance to file an appeal (another opportunity to fight the Butler Act), he actually asked the jury to find Scopes guilty.

Why was Scopes arrested?

The ACLU was notified of the plan, and Scopes was arrested for violating the Butler Act on May 7, 1925. Scopes appeared before the Rhea County justice of the peace on May 9, 1925, and was formally charged with having violated the Butler Act—a misdemeanor. He was released on bond, paid for by local businessmen.

Why did the judge take the unusual step of hearing the testimony without the jury present?

But because the prosecution objected to the use of expert testimony, the judge took the unusual step of hearing the testimony without the jury present. Metcalf explained that nearly all of the prominent scientists he knew agreed that evolution was a fact, not merely a theory.

What was the name of the trial in Tennessee?

The Scopes "Monkey" Trial (official name is State of Tennessee v John Thomas Scopes) began on July 10, 1925, in Dayton, Tennessee. On trial was science teacher John T. Scopes, charged with violating the Butler Act, which prohibited the teaching of evolution in Tennessee public schools. Known in its day as "the trial of the century," ...

When was the Scopes Trial made into a movie?

A fictionalized version of the Scopes Trial, Inherit the Wind, was made into a play in 1955 and a well-received movie in 1960. The Butler Act remained on the books until 1967, when it was repealed. Anti-evolution statutes were ruled unconstitutional in 1968 by the U.S. Supreme Court in Epperson v Arkansas.

What was the first day of the Butler Act trial?

The first day of the trial was spent selecting the jury and was followed by a weekend recess. The next two days involved debate between the defense and prosecution as to whether the Butler Act was unconstitutional, which would thereby place doubt on the validity of Scopes' indictment.

How could Scopes have avoided a criminal trial?

Ironically Scopes could have avoided a criminal trial with its possible conviction and loss of a job by taking advantage of his status as a professional educator, questioning the constitutionality of the anti-evolution law, and asking for a declaratory judgment (Larson 60).

Why did Judge Raulston allow Scopes to be indicted?

Because Judge Raulston had been so eager to get the case that he had allowed Scopes to be indicted on May 25th by a grand jury whose term had expired, the judge convened another grand jury to indict Scopes a second time (Ginger 129). Eight prospective jurors were examined and excused for various reasons.

Why was Scopes not called to the witness stand?

Scopes was not called to the witness stand because, as Darrow explained to Judge Raulston, “Your honor, every single word that was said against this defendant, everything was true” ( Trial 133).

Why was Scopes conscripted?

Because so few reporters were present when Bryan took the stand to be interrogated by Darrow, Scopes was conscripted to write covering news stories for the delinquent newsmen (Scopes 183-184). Much of the Scopes Trial news coverage in 1925 and ever since leaves a great deal to be desired.

How long is the scopes trial festival?

Since 1988, Bryan College and the Dayton community have cooperated in organizing a four-day Scopes Trial Festival whose main feature is a documentary drama based almost entirely on the transcript of the trial and performed in the Scopes Trial courtroom.

What was the most famous court case in Rhea County?

By far the most celebrated court case in Rhea County and perhaps in all of Tennessee history was the case of the State of Tennessee vs. John Thomas Scopes , which took place in Dayton’s Rhea County Courthouse 10-21 July 1925. For the most part, the trial has been misreported and misinterpreted by journalists at the time of the trial and ever since, by historians who depended on the journalists more than on the official records and actual participants, and by audiences of the play, film, and television versions of Inherit the Wind, who rarely read the authors’ disclaimer in their preface: “ Inherit the Wind is not history” (Lawrence and Lee ix).

What is the scopes evolution trial?

The Scopes Evolution Trial was a world-class event in its day, and it continues to attract inquiries and visitors from all over the United States and many parts of the world. It has become the benchmark for subsequent trials dealing with similar problems which are usually dubbed “Scopes II” by the press.

Who was John Scopes?

John Scopes, a young popular high school science teacher, agreed to stand as defendant in a test case to challenge the law. He was arrested on May 7, 1925, and charged with teaching the theory of evolution. Clarence Darrow, an exceptionally competent, experienced, and nationally renowned criminal defense attorney led the defense along ...

How much was John Scopes fined?

John Scopes was fined $100. The ACLU hoped to use the opportunity as a chance to take the issue all the way to the Supreme Court, but the verdict was reversed by state supreme court on a technicality.

What was the purpose of the monkey trial?

ACLU History: The Scopes 'Monkey Trial'. In March 1925, the Tennessee state legislature passed a bill that banned the teaching of evolution in all educational institutions throughout the state. The Butler Act set off alarm bells around the country. The ACLU responded immediately with an offer to defend any teacher prosecuted under the law.

What was John Scopes' strategy?

His strategy was quite simple: to prove John Scopes guilty of violating Tennessee law. The Scopes trial turned out to be one of the most sensational cases in 20th century America; it riveted public attention and made millions of Americans aware of the ACLU for the first time.

Who was Susan Epperson?

An opportunity finally arose, more than four decades later, when the ACLU filed an amicus brief on behalf of Susan Epperson, a Zoology teacher in Arkansas, who challenged a state ban on teaching 'that mankind ascended or descended from a lower order of animals.'. In 1968, the Supreme Court, in Epperson v.

Who was John Thomas Scopes?

Defending substitute high school teacher John Thomas Scopes was Clarence Darrow, one of the celebrity lawyers of the day. William Jennings Bryan—the “Great Commoner,” three-time Democratic nominee for President, and Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. ruling elder—argued for the prosecution, the State of Tennessee, ...

Who was the secretary of state under Woodrow Wilson?

Charles Wishart, RG 414. (Image No. 4725) A convert to Presbyterianism, Bryan had served as Secretary of State under fellow Presbyterian Woodrow Wilson.

What was the fine for Scopes?

Scopes was found guilty and ordered to pay the minimum fine of $100. A year later, the Tennessee Supreme Court reversed the decision of the Dayton court on a procedural technicality—not on constitutional grounds, as Darrow had hoped. According to the court, the fine should have been set by the jury, not Raulston.

How long did John Caverly sentence Leopold and Loeb?

Darrow succeeded. Caverly sentenced Leopold and Loeb to life in prison plus 99 years.

Who is Ruby Hammerstrom?

( m. 1903) . Children. 1. Relatives. J. Howard Moore (brother-in-law) Clarence Seward Darrow ( / ˈdæroʊ /; April 18, 1857 – March 13, 1938) was an American lawyer who became famous in the early 20th century for his involvement in the Leopold and Loeb murder trial and the Scopes "Monkey" Trial.

Who was Darrow married to?

Darrow married Jessie Ohl in April 1880. They had one child, Paul Edward Darrow, in 1883. They were divorced in 1897. Darrow later married Ruby Hammerstrom, a journalist 16 years his junior, in 1903. They had no children.

When was Attorney for the Damned published?

"Attorney for the Damned" (Arthur Weinberg, ed), published by University of Chicago Press in 2012 ; Simon and Schuster in 1957; provides Darrow's most influential summations and includes scene-setting explanations and comprehensive notes; on NYT best seller list 19 weeks.

Who was the first person to be executed for murder?

Also in 1894, Darrow took on the first murder case of his career, defending Patrick Eugene Prendergast, the "mentally deranged drifter" who had confessed to murdering Chicago mayor Carter Harrison, Sr. Darrow's "insanity defense" failed and Prendergast was executed that same year.

Did Clarence Darrow graduate from law school?

The young Clarence attended Allegheny College and the University of Michigan Law School, but did not graduate from either institution. He attended Allegheny College for only one year before the Panic of 1873 struck, and Darrow was determined not to be a financial burden to his father any longer.

Overview

Dayton, Tennessee

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) offered to defend anyone accused of teaching the theory of evolution in defiance of the Butler Act. On April 5, 1925, George Rappleyea, local manager for the Cumberland Coal and Iron Company, arranged a meeting with county superintendent of schools Walter White and local attorney Sue K. Hicks at Robinson's Drug Store, convincing them that the controversy of such a trial would give Dayton much needed publicity. …

Origins

State Representative John Washington Butler, a Tennessee farmer and head of the World Christian Fundamentals Association, lobbied state legislatures to pass anti-evolution laws. He succeeded when the Butler Act was passed in Tennessee, on March 25, 1925. Butler later stated, "I didn't know anything about evolution ... I'd read in the papers that boys and girls were coming home from school and telling their fathers and mothers that the Bible was all nonsense." Tennessee governor Austin Peay signed the law to gain support among rural legislators, but believ…

Proceedings

The ACLU had originally intended to oppose the Butler Act on the grounds that it violated the teacher's individual rights and academic freedom, and was therefore unconstitutional. Principally because of Clarence Darrow, this strategy changed as the trial progressed. The earliest argument proposed by the defense once the trial had begun was that there was actually no conflict between evolution and the creation account in the Bible; later, this viewpoint would be …

Appeal to the Supreme Court of Tennessee

Scopes' lawyers appealed, challenging the conviction on several grounds. First, they argued that the statute was overly vague because it prohibited the teaching of "evolution", a very broad term. The court rejected that argument, holding:

Evolution, like prohibition, is a broad term. In recent bickering, however, evolution has been understood to mean the theory which holds that man has developed from some pre-existing lower type. This is the popular significan…

Aftermath

The trial revealed a growing chasm in American Christianity and two ways of finding truth, one "biblical" and one "evolutionist". Author David Goetz writes that the majority of Christians denounced evolution at the time.

Author Mark Edwards contests the conventional view that in the wake of the Scopes trial, a humiliated fundamentalism retreated into the political and cultural background, a viewpoint which is evidenced in the film Inherit the Wind (1960) as well as in the majority of contemporary historical accounts. Rather, the cause of funda…

Publicity

Edward J. Larson, a historian who won the Pulitzer Prize for History for his book Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America's Continuing Debate Over Science and Religion (2004), notes: "Like so many archetypal American events, the trial itself began as a publicity stunt." The press coverage of the "Monkey Trial" was overwhelming. The front pages of newspapers like The New York Times were dominated by the case for days. More than 200 newspaper reporters from all parts of the country and two from London were in Dayton. Twenty-two

Courthouse

In a $1 million restoration of the Rhea County Courthouse in Dayton, completed in 1979, the second-floor courtroom was restored to its appearance during the Scopes trial. A museum of trial events in its basement contains such memorabilia as the microphone used to broadcast the trial, trial records, photographs, and an audiovisual history. Every July, local people re-enact key moments of the trial in the courtroom. In front of the courthouse stands a commemorative pla…

Darwin's Theory and The Butler Act

Arrest of John T. Scopes

- The citizens of Dayton were not merely trying to protect biblical teachings with their arrest of Scopes; they had other motives as well. Prominent Dayton leaders and businessmen believed that the ensuing legal proceedings would draw attention to their little town and provide a boost to its economy. These businessmen had alerted Scopes to the ad placed by the ACLU and convinced him to stand trial. Scopes, in fact, usually taught math and c…

A Legal Dream Team

- Both the prosecution and the defense secured attorneys that would be certain to attract news media to the case. William Jennings Bryan—a well-known orator, secretary of state under Woodrow Wilson, and three-time presidential candidate—would head the prosecution, while prominent defense attorney Clarence Darrow would lead the defense. Although polit...

State of Tennessee V John Thomas Scopes Begins

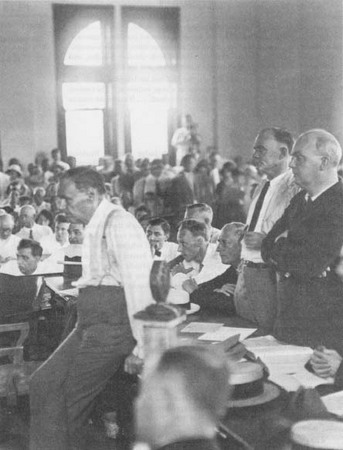

- The trial began at the Rhea County courthouse on Friday, July 10, 1925, in a sweltering second-floor courtroom packed with more than 400 observers. Darrow was astonished that the session began with a minister reading a prayer, especially given that the case featured a conflict between science and religion. He objected but was overruled. A compromise was struck, in which fundamentalist and non-fundamentalist clergy would alternate re…

Kangaroo Court

- On July 15, Scopes entered his plea of not guilty. After both sides gave opening arguments, the prosecution went first in presenting its case. Bryan's team set out to prove that Scopes had indeed violated Tennessee law by teaching evolution. Witnesses for the prosecution included the county school superintendent, who confirmed that Scopes had taught evolution out of A Civic Biology, the state-sponsored textbook cited in the case. Two student…

Cross-Examination of William Jennings Bryan

- Unable to call any of his expert witnesses to testify for the defense, Darrow made the highly unusual decision to call prosecutor William Jennings Bryan to testify. Surprisingly—and against the advice of his colleagues—Bryan agreed to do so. Once again, the judge inexplicably ordered the jury to leave during the testimony. Darrow questioned Bryan on various biblical details, including whether he thought the Earth had been created in six days…

Verdict

- On the morning of Tuesday, July 21, Darrow asked to address the jury before they left to deliberate. Fearing that a not guilty verdict would rob his team of the chance to file an appeal (another opportunity to fight the Butler Act), he actually asked the jury to find Scopes guilty. After only nine minutes of deliberation, the jury did just that. With Scopes having been found guilty, Judge Raulston imposed a fine of $100. Scopes came forward and politely tol…

Aftermath

- Five days after the trial ended, the great orator and statesman, William Jennings Bryan, still in Dayton, died at the age of 65. Many said he died of a broken heart after his testimony had cast doubt upon his fundamentalist beliefs, but he had actually died of a stroke likely brought on by diabetes. A year later, Scopes' case was brought before the Tennessee Supreme Court, which upheld the constitutionality of the Butler Act. Ironically, the court overturne…

Popular Posts:

- 1. civil litigation lawyer free consultation

- 2. arthur meighen who was a successful trial lawyer.

- 3. how to become a nc lawyer

- 4. the bet by anton chekhov what did the lawyer do in jail

- 5. what type of lawyer do i need when i break contract

- 6. what majors would a family court lawyer take?

- 7. how many epdosides medalist lawyer heir

- 8. who does worker's comp lawyer work for

- 9. teresa shook, a lawyer and educator who founded the women's march movement

- 10. what does a juris doctor lawyer do