Did Gandhi work as a lawyer in South Africa?

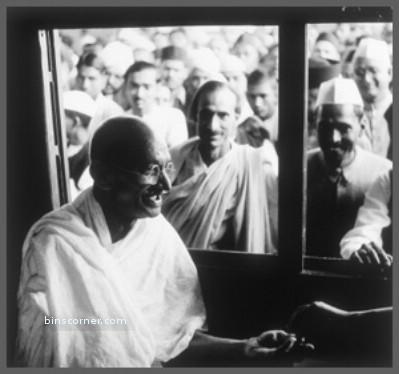

Gandhi in South Africa. After struggling to find work as a lawyer in India, Gandhi obtained a one-year contract to perform legal services in South Africa. In April 1893, he sailed for Durban in the South African state of Natal.

Who followed Gandhi in South Africa?

Gandhi was followed by two parties led by Thambi Naidoo and Albert Christopher. This marked one of the greatest episodes in South African history. He was arrested the following day at Palmford.

What is the significance of Gandhi's years in South Africa?

For those interested in the Gandhi story, his years in South Africa were an important chapter in his path to becoming a leading political figure of the 20th century; there are many touch points and sites of interest on the road the young Gandhi followed in this country. Monument to Mahatma Gandhi imprisoned here.

When did Mahatma Gandhi become a lawyer?

The Dismal State of British Legal Training The world of legal education into which Gandhi stepped in the fall of 1888 would be almost unrecognizable to legal educators today. It is now almost universally true that there is a serious academic component in one's training for the bar, usually in a university context.

Which country did Mahatma Gandhi go to as a young lawyer?

For 20 years before he got involved in the freedom struggle, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was a lawyer in South Africa, a profession common among the ranks of India's freedom fighters, from Lala Lajpat Rai to Jawaharlal Nehru. And yet, it is a profession that hardly seems to fit the man.

Was Gandhi a lawyer in South Africa?

In April 1893, Gandhi aged 23, set sail for South Africa to be the lawyer for Abdullah's cousin. He spent 21 years in South Africa, where he developed his political views, ethics and politics.

When did Gandhi go to South Africa?

1893Born in India and educated in England, Gandhi traveled to South Africa in early 1893 to practice law under a one-year contract. Settling in Natal, he was subjected to racism and South African laws that restricted the rights of Indian laborers.

Who is Mahatma Gandhi?

Gandhi's Life as a Lawyer Revealed. Mahatma Gandhi is widely recognized as a leader of Indian nationalism in British-ruled India who employed nonviolent civil disobedience, inspiring movements for civil rights across the world. A professor at West Virginia University’s College of Law recently published book that explores a side ...

What was Gandhi's practice?

By the end his practice, his entire practice is devoted to his political, moral, and spiritual beliefs. And at that point he becomes integrated.

What did Disalvo ask himself?

Disalvo says he had to ask himself if there was a connection between Gandhi’s practice of law and the development of his philosophy. He also wondered, why hasn’t anybody explored this?’

Why did Gandhi withdraw from the case?

“In fact in one of his first cases in India where he tried to launch a practice and failed, he had to basically withdraw from the case because he was too nervous in court!” . DiSalvo remarks.

Who is the leader of Indian nationalism?

Charles R. DiSalvo in his office at the College of Law at West Virginia University. Mahatma Gandhi is widely recognized as a leader of Indian nationalism in British-ruled India who employed nonviolent civil disobedience, inspiring movements for civil rights across the world.

Who is the author of The Man Before the Mahatma?

Author and Woodrow A. Potesta professor of law , Charles R. DiSalvo, recently read excerpts of his new book The Man Before The Mahatma: M.K. Gandhi, Attorney at Law in Morgantown. First published by Random House India, and most recently by University of California Press, DiSalvo says producing this work that explores Gandhi’s early life in South Africa has been a goal since he discovered that Gandhi was in fact a lawyer for 25 years before becoming a pacifist reformer in India.

Who gave credit to Gandhi?

DiSalvo gives much credit to the many law and history students who read through some 10,000 newspapers from South Africa which held keys to unlocking details of Gandhi’s career as a lawyer and a politician. DiSalvo says it was that Herculean effort that perhaps prevented anyone else from writing this book earlier.

Where did Gandhi study law?

Gandhi had studied law, not in his native India, but London . He’d moved there in 1888, and it’s curiously jarring to think that while Jack the Ripper was stalking the shadows of Whitechapel, the young Gandhi was settling elsewhere in the city to read law, take dancing lessons and become a campaigner for vegetarianism (one of his friends in the cause was Arnold Hills, who’d go on to found West Ham United).

Where did Gandhi work?

London proved to be an exciting, welcoming city for Gandhi. It was a few years later, when he arrived to work as a law clerk in South Africa in 1893, that he had his rude awakening about what it meant to be a brown man in the British Empire.

What was Gandhi's service called?

Interestingly, despite his burgeoning activism, Gandhi still felt a deep-seated loyalty for the Empire – a fact that led to him forming a stretcher-carrying service called the Natal Indian Ambulance Corps to aid British troops during the Second Boer War.

Why was Satyagraha encouraged by Gandhi?

Satyagraha was encouraged by Gandhi as a way to defy the Asiatic Registration Act, which required Indians in South Africa to be thumb-printed and constantly carry registration documents with them. Gandhi encouraged mass defiance of this law, and was himself jailed multiple times for refusing to conform.

What did Gandhi do to help the Indians?

Although the bill was passed, Gandhi’s campaign shone a light onto the grievances of the Indian population in South Africa, and he went on to help create the Natal Indian Congress that same year.

Why was Gandhi awarded the medals?

Gandhi himself was awarded medals by the British for his brave work on the frontlines. However, in the early 1900s, Gandhi founded Indian Opinion, a newspaper that would carry articles arguing for greater civil liberties and rights for Indians in South Africa.

What was Gandhi's attitude towards black people?

His attitude towards black people in South Africa has been slammed as dismissive, aloof and downright racist. Some historians have argued that Gandhi regarded black Africans with the same withering contempt that many white colonialists did, citing his use of the derogatory word 'kaffir' and other troubling remarks.

Where did Gandhi go to practice law?

Gandhi successfully completed his degree at the Inner Temple and was called to the Bar on 10 June 1891. He enrolled in the High Court of London; but later that year he left for India. For the next two years, Gandhi attempted to practice law in India, establishing himself in the legal profession in Bombay. Unfortunately, he found that he lacked both knowledge of Indian law and self-confidence at trial. His practice collapsed and he returned home to Porbandar. It was while he was contemplating his seemingly bleak future that a representative of an Indian business firm situated in the Transvaal (now Gauteng ), South Africa offered him employment. He was to work in South Africa for a period of 12 months for a fee of £105.00.

Why did Gandhi stay in Johannesburg?

Gandhi failed in his mission to win Chamberlain’s sympathy and discovered in the process that the situation in the Transvaal had become ominous for the Indians. He therefore decided to stay on in Johannesburg and enrolled as an advocate of the Supreme Court.Though he stayed on specifically to challenge White arrogance and to resist injustice, he harboured no hatred in his heart and was in fact always ready to help when they were in distress. It was this rare combination of readiness to resist wrong and capacity to love his opponent which baffled his enemies and compelled their admiration.When the Zulu rebellion broke out, he again offered his help to the Government and raised an Indian Ambulance Corps. He was happy that he and his men had to nurse the sick and dying Zulus whom the White doctors and nurses were unwilling to touch.Gandhi was involved in the formation British Indian Association (BIA) in 1903. The movement was to prevent proposed evictions of Indians in the Transvaal under British leadership. According to Arthur Lawley, the newly appointed Lieutenant Governor Lord Alfred Milner said that Whites were to be protected against Indians in what he called a 'struggle between East and West for the inheritance of the semi-vacant territories of South Africa'.

What did Gandhi do during his time in Pretoria?

During his stay in Pretoria, Gandhi read about 80 books on religion. He came under the influence of Christianity but refused to embrace it. During this period, Gandhi attended Bible classes.Within a week of his arrival there, Gandhi made his first public speech making truthfulness in business his theme. The meeting was called to awaken the Indian residents to a sense of the oppression they were suffering under. He took up the issue of Indians in regard to first class travel in railways. As a result, an assurance was given that first and second-class tickets would be issued to Indians "who were properly dressed". This was a partial victory.These incidents lead Gandhi to develop the concept of Satyagraha. He united the Indians from different communities, languages and religions, who had settled in South Africa.By the time Gandhi arrived in South Africa the growing national- perpetuated by the White ruling authorities and the majority of the White citizenry - anti-Indian attitude had spread to Natal (now kwaZulu-Natal). The first discriminatory legislation directed at Indians, Law 3 of 1885, was passed in the South African Republic, or the Transvaal. The right to self-government had been granted to Natal in 1893 and politicians were increasing pressure to pass legislation aimed at containing the 'merchant [Indian] menace'.

How did Gandhi work on the Natal Legislative Assembly?

Gandhi immediately turned the farewell dinner into a meeting and an action committee was formed. This committee then drafted a petition to the Natal Legislative Assembly. Volunteers came forward to make copies of the petition and to collect signatures - all during the night. The petition received much favourable publicity in the press the following morning. The bill was however passed. Undeterred, Gandhi set to work on another petition to Lord Ripon, the Secretary of State for Colonies. Within a month the mammoth petition with ten thousand signatures was sent to Lord Ripon and a thousand copies printed for distribution. Even The Times admitted the justice of the Indian claim and for the first time the people in India came to know of the oppressive lot of their compatriots in South Africa.

Why did Gandhi leave the Black Act?

The Indians made a bonfire of their registration certificates and decided to defy the ban. In June 1909, he left for London after having defended his position as leader of the Transvaal merchant community.Gandhi returned to South Africa in December 1909 to find that members of the NIC were openly plotting against him. He was fighting for his political survival and withdrew to Tolstoy, a farm he had purchased in 1910 to support the families of jailed passive resisters. Gandhi only came under the public eye again in 1912 as a result of a visit to South Africa by Indian statesman Gopal Krishna Gokhale. He was accused of preventing opponents of his policies to speak with the visitor and finally, on 26 April 1913 Gandhi and his rivals in the NIC went their separate ways.

Why was Gandhi involved in the British Indian Association?

The movement was to prevent proposed evictions of Indians in the Transvaal under British leadership.

How many volunteers did Gandhi train?

He organized and, with the help of a Dr. Booth, trained an Indian Ambulance Corps of 1,100 volunteers and offered its services to the Government. The corps under Gandhi’s leadership rendered valuable service and was mentioned in dispatches.In 1901, at the end of the war, Gandhi wanted to return to India.

Who advised Gandhi to study law?

Mavji Dave Joshiji, a Brahmin priest and family friend, advised Gandhi and his family that he should consider law studies in London. In July 1888, his wife Kasturba gave birth to their first surviving son, Harilal. His mother was not comfortable about Gandhi leaving his wife and family, and going so far from home.

What did Gandhi do in 1921?

Assuming leadership of the Indian National Congress in 1921, Gandhi led nationwide campaigns for easing poverty, expanding women's rights, building religious and ethnic amity, ending untouchability, and above all for achieving swaraj or self-rule.

Why did Gandhi resign from Congress?

He did not disagree with the party's position but felt that if he resigned, his popularity with Indians would cease to stifle the party's membership, which actually varied, including communists, socialists, trade unionists, students, religious conservatives, and those with pro-business convictions, and that these various voices would get a chance to make themselves heard. Gandhi also wanted to avoid being a target for Raj propaganda by leading a party that had temporarily accepted political accommodation with the Raj.

How did Gandhi change his mind?

This changed, however, after he was discriminated against and bullied, such as by being thrown out of a train coach because of his skin colour by a white train official. After several such incidents with Whites in South Africa, Gandhi's thinking and focus changed, and he felt he must resist this and fight for rights. He entered politics by forming the Natal Indian Congress. According to Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed, Gandhi's views on racism are contentious, and in some cases, distressing to those who admire him. Gandhi suffered persecution from the beginning in South Africa. Like with other coloured people, white officials denied him his rights, and the press and those in the streets bullied and called him a "parasite", "semi-barbarous", "canker", "squalid coolie", "yellow man", and other epithets. People would spit on him as an expression of racial hate.

What did Gandhi do to the common Indians?

Bringing anti-colonial nationalism to the common Indians, Gandhi led them in challenging the British-imposed salt tax with the 400 km (250 mi) Dandi Salt March in 1930 and in calling for the British to quit India in 1942. He was imprisoned many times and for many years in both South Africa and India.

Why did Gandhi raise Indian volunteers?

Gandhi raised eleven hundred Indian volunteers, to support British combat troops against the Boers.

How did Gandhi influence his life?

Gandhi's time in London was influenced by the vow he had made to his mother. He tried to adopt "English" customs, including taking dancing lessons. However, he did not appreciate the bland vegetarian food offered by his landlady and was frequently hungry until he found one of London's few vegetarian restaurants. Influenced by Henry Salt's writing, he joined the London Vegetarian Society and was elected to its executive committee under the aegis of its president and benefactor Arnold Hills. An achievement while on the committee was the establishment of a Bayswater chapter. Some of the vegetarians he met were members of the Theosophical Society, which had been founded in 1875 to further universal brotherhood, and which was devoted to the study of Buddhist and Hindu literature. They encouraged Gandhi to join them in reading the Bhagavad Gita both in translation as well as in the original.

What did Gandhi do in South Africa?

In this year, he undertook a journey to India to launch a protest campaign on behalf of Indians in South Africa. It took the form of letters written to newspapers, interviews with leading nationalist leaders and a number of public meetings. His mission caused great uproar in India and consternation among British authorities in England and Natal. Gandhi embarrassed the British Government enough to cause it to block the Franchise Bill in an unprecedented move, which resulted in anti-Indian feelings in Natal reaching dangerous new levels.

Why did Gandhi stay in Johannesburg?

But the Colonial Secretary who had come to receive a gift of thirty-five million pounds from South Africa had no intention to alienate the European community. Gandhi failed in his mission to win Chamberlain’s sympathy and discovered in the process that the situation in the Transvaal had become ominous for the Indians. He therefore decided to stay on in Johannesburg and enrolled as an advocate of the Supreme Court.

Why was Gandhi involved in the British Indian Association?

The movement was to prevent proposed evictions of Indians in the Transvaal under British leadership. According to Arthur Lawley, the newly appointed Lieutenant Governor Lord Alfred Milner said that Whites were to be protected against Indians in what he called a ‘struggle between East and West for the inheritance of the semi-vacant territories of South Africa’.

How did Gandhi work on the Natal Legislative Assembly?

Gandhi immediately turned the farewell dinner into a meeting and an action committee was formed. This committee then drafted a petition to the Natal Legislative Assembly. Volunteers came forward to make copies of the petition and to collect signatures – all during the night. The petition received much favourable publicity in the press the following morning. The bill was however passed. Undeterred, Gandhi set to work on another petition to Lord Ripon, the Secretary of State for Colonies. Within a month the mammoth petition with ten thousand signatures was sent to Lord Ripon and a thousand copies printed for distribution. Even The Times admitted the justice of the Indian claim and for the first time the people in India came to know of the oppressive lot of their compatriots in South Africa.

Why did Gandhi hide the insult?

Gandhi hid the insult for fear of missing the coach altogether. Along the way, a conductor who wanted smoke put a piece of dirty bag on the footstool and ordered Gandhi to sit down and let the conductor sit on his place. Gandhi refused. The conductor swore and started hitting him, trying to throw him down.

What compartment was Gandhi in?

There, Gandhi was seated in the first-class compartment, as he had purchased a first-class ticket. A White person who entered the compartment hastened to summon the White railway officials, who ordered Gandhi to remove himself to the van compartment, since ‘coolies’ (a racist term for Indians) and non-whites were not permitted in first-class compartments. Gandhi protested and issued his ticket, but he was warned that he would be forcibly removed if he did not make a gracious exit. As Gandhi refused to comply with the order, a White police officer pushed him out of the train, and his luggage was tossed out on to the platform. The train steamed away, and Gandhi retreated to the waiting room.

What was Gandhi's role in the Indian campaign?

As a talented letter-writer and meticulous planner, he was assigned the task of compiling all petitions, arranging meetings with politicians and addressing letters to newspapers. He also campaigned in India and made an, initially, successful appeal to the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord Ripon. He was instrumental in the formation of theNatal Indian Congress (NIC) on 22 August 1894, which marked the birth of the first permanent political organisation to strive to maintain and protect the rights of Indians in South Africa.

How did Gandhi break the law?

By the time he arrived 24 days later in the coastal town of Dandi, the ranks of the marchers swelled, and Gandhi broke the law by making salt from evaporated seawater. The Salt March sparked similar protests, and mass civil disobedience swept across India.

Who convinced Gandhi to stay and lead the fight against the legislation?

Fellow immigrants convinced Gandhi to stay and lead the fight against the legislation. Although Gandhi could not prevent the law’s passage, he drew international attention to the injustice. After a brief trip to India in late 1896 and early 1897, Gandhi returned to South Africa with his wife and children.

How many children did Gandhi have?

In 1885, Gandhi endured the passing of his father and shortly after that the death of his young baby. In 1888, Gandhi’s wife gave birth to the first of four surviving sons. A second son was born in India 1893. Kasturba gave birth to two more sons while living in South Africa, one in 1897 and one in 1900.

Why did Gandhi form the Natal Indian Congress?

Gandhi formed the Natal Indian Congress in 1894 to fight discrimination.

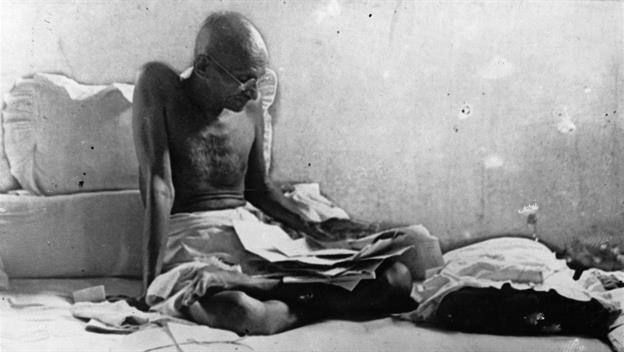

What did Gandhi study?

Living in South Africa, Gandhi continued to study world religions . “The religious spirit within me became a living force,” he wrote of his time there. He immersed himself in sacred Hindu spiritual texts and adopted a life of simplicity, austerity, fasting and celibacy that was free of material goods.

Why did Gandhi fast for 3 weeks?

When violence between the two religious groups flared again, Gandhi began a three-week fast in the autumn of 1924 to urge unity. He remained away from active politics during much of the latter 1920s.

What religion did Gandhi follow?

Gandhi’s Religion and Beliefs. Gandhi grew up worshiping the Hindu god Vishnu and following Jainism, a morally rigorous ancient Indian religion that espoused non-violence, fasting, meditation and vegetarianism.

Why did Gandhi not become a lawyer?

Despite these contradictions, Gandhi wasn’t a lawyer simply by training, giving up practice in a few years because of disillusionment, intent on doing greater things – it was something he stuck at for a very long time, moving countries and continents to find a way to make it work.

What happened to Gandhi when he tried to press his brother's case?

When he continued to try to press his brother’s case, the agent had Gandhi thrown out of the room by his peon. Gandhi was furious at this (!) and threatened to take action against the officer.

How did the Dada Abdulla case affect Gandhi?

In addition to the contribution of the Dada Abdulla case to Gandhi’s idealisation of truth, it changed the way he approached disputes in general. Rather than fight the case out in court which would involve more time and expenses, Gandhi thought it would be better to tackle the case in an arbitration.

Why did Gandhi stay on the Natal bill?

Gandhi was supposed to return to India after the conclusion of the case, but during the farewell dinner hosted for him by Dada Abdulla in Durban, conversation turned to the Bill in the Natal legislature which sought to prevent Indians from voting in elections there. Gandhi was persuaded to stay on and help fight this discriminatory measure, and this cemented his interest and passion for what he called ‘public work’, and how he thought it should be done.

Where did Gandhi go to live?

After failing to establish himself in Bombay, Gandhi was forced to return home to Rajkot (his family home was in Porbandar but the household was based in Rajkot). Here, through the influence of his brother’s partner (the two of them had a small legal practice), he was able to do “moderately well” for himself, drafting petitions for clients in civil matters – though oral arguments in court were still beyond him.

What is Bombay High Court famous for?

The Bombay High Court is one of the most beautiful courts in the country, famed for its neo-Gothic architecture and a favourite among legal interns looking for an impressive selfie. Take a trip to its courtrooms over the years and you’d be witness to arguments from some of the most famous names of the Indian bar, from Badruddin Tyabji to Ram Jethmalani, and from Nani Palkhivala to Indira Jaising, by way of Fali Nariman.

How did Gandhi get involved in the case of Abdulla?

Gandhi’s opportunity to get involved in the case arose as Abdulla’s records were in Gujarati – since he knew the language and was a London-trained barrister, he could bridge the language divide for the British lawyers representing Abdulla in court. He reached Durban on 24 May 1893, and travelled further to Pretoria where the case was being heard.

How did Gandhi influence the South African people?

11 His efforts paved the way for a change in policy. In fact, the Gandhian influence dominated freedom struggles on the African continent right up to the 1960s because of the power it generated and the unity it forged among the usually powerless. Nonviolence was the official stance of all major African coalitions, and the South African African National Congress (ANC) remained implacably opposed to violence for most of its existence. 12 South Africa because of apartheid was placed on the agenda of the United Nations for the first time in 1946 by India regarding the treatment of people of Indian origin living in South Africa. 13 South Africa’s apartheid policies clearly violated provisions of the U.N. Charter and human rights instruments adopted pursuant to it. 14. Apartheid has also negatively impacted relations between the Republic of South Africa and India because of the subordinate status of people of Indian decent in South Africa. 15 The General Assembly highlighted the deficit of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in the apartheid policy within South Africa. Thanks to the work of Gandhi and s atyagraha, the world took notice of inequalities caused by South African discriminatory policies.

What was Gandhi's goal in 1907?

6 By this time, Gandhi had realized his overreaching life goal of saradaya which means the “welfare of all” and or “to lift of all”. The Indian terms describing these principles are satya (truth), ahimsa (nonviolence), and tapasya, (selfsuffering). 7 Gandhi used this idea in response to the Black Act. He and other members of the satyagraha (truth and nonviolent disobedience) movement picketed outside of the registration offices; these actions led to the arrest of the leaders of the movement. 8 This was Gandhi’s first arrest for disobedience; he was sentenced on January 10, 1908, to two months of simple imprisonment. 9 This was the first of six arrests in South Africa; three of with involving failure to produce registration. 10

Origins

Diet

- In 1906, believing that family life was taking away from his full potential as a public advocate, Gandhi took the vow of brahmacharya (a vow of abstinence against sexual relations, even with one's own wife). This was not an easy vow for him to follow, but one that he worked diligently to keep for the rest of his life. Thinking that one passion fed others, Gandhi decided to restrict his d…

Timeline

- On 28 December 1907 the first arrests of Indians refusing to register were made, and by the end of January 1908, 2000 Asians had been jailed. Gandhi had also been jailed several times, but many key figures in the movement fled the colony rather than be arrested. The first time Gandhi officially used Satyagraha was in South Africa beginning in 1907 ...

Trial

- The Indians made a bonfire of their registration certificates and decided to defy the ban on immigration to the Transvaal. Jails began to be filled. Gandhi was arrested a second time in September 1908 and sentenced to two months' imprisonment, this time hard labour. The struggle continued. In February 1909 he was arrested a third time and sentenced to three months' hard la…

Later life

- Gandhi registered, but his disappointment was great when Smuts went back on his word and refused to repeal the Black Act along with denying any promises were made. The Indians made a bonfire of their registration certificates and decided to defy the ban. In June 1909, he left for London after having defended his position as leader of the Transvaal merchant community.Gan…

Causes

- In 1911, a provisional settlement of the Asiatic question in the Transvaal brought about a suspension of the Satyagraha campaign. In the following year, Gokhale visited South Africa and on the eve of his departure assured Gandhi that the Union Government had promised to repeal the Black Act, to remove the racial bar from the immigration law and to abolish the £3 tax. But Gand…

Impact

- At one time there were about fifty thousand indentured labourers on strike and several thousand other Indians in jail. The Government tried repression and even shooting, and many lives were lost. \"In the end\", as an American biographer has put it, \"General Smuts did what every Government that ever opposed Gandhi had to do - he yielded.\" A spontaneous strike by Indians i…

Quotes

- Recalling the gift twenty-five years later, the General wrote: I have worn these sandals for many a summer since then even though I may feel that I am not worthy to stand in the shoes of so great a man.

Title

- It was during his first year back in India that Gandhi was given the honorary title of Mahatma (\"Great Soul\"). Many credit Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore, winner of the 1913 Nobel Prize for Literature, for both awarding Gandhi of this name and of publicising it. The title represented the feelings of the millions of Indian peasants who viewed Gandhi as a holy man. However, Gandhi n…

Details

- On 30 January 1948, Gandhi hurriedly went up the few steps of the prayer ground in a large park in Delhi. He had been detained by a conference with the Deputy Prime Minister, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, and was late by a few minutes. He loved punctuality and was worried that he had kept the congregation waiting. \"I am late by ten minutes,\" he murmured. \"I should be here at the stroke …

Overview

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist and political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful campaign for India's independence from British rule, and to later inspire movements for civil rights and freedom across the world. The honorific Mahātmā (Sanskrit: "great-souled", "venerable"), first applied to him in 1914 in South Africa, …

Biography

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on 2 October 1869 into a Gujarati Hindu Modh Bania family in Porbandar (also known as Sudamapuri), a coastal town on the Kathiawar Peninsula and then part of the small princely state of Porbandar in the Kathiawar Agency of the Indian Empire. His father, Karamchand Uttamchand Gandhi (1822–1885), served as the dewan (chief minister) of Porb…

Principles, practices, and beliefs

Gandhi's statements, letters and life have attracted much political and scholarly analysis of his principles, practices and beliefs, including what influenced him. Some writers present him as a paragon of ethical living and pacifism, while others present him as a more complex, contradictory and evolving character influenced by his culture and circumstances.

Literary works

Gandhi was a prolific writer. His signature style was simple, precise, clear and as devoid of artificialities. One of Gandhi's earliest publications, Hind Swaraj, published in Gujarati in 1909, became "the intellectual blueprint" for India's independence movement. The book was translated into English the next year, with a copyright legend that read "No Rights Reserved". For decades he edited …

Legacy and depictions in popular culture

• The word Mahatma, while often mistaken for Gandhi's given name in the West, is taken from the Sanskrit words maha (meaning Great) and atma (meaning Soul). Rabindranath Tagore is said to have accorded the title to Gandhi. In his autobiography, Gandhi nevertheless explains that he never valued the title, and was often pained by it.

See also

• Gandhi cap

• Gandhi Teerth – Gandhi International Research Institute and Museum for Gandhian study, research on Mahatma Gandhi and dialogue

• Inclusive Christianity

• List of civil rights leaders

Bibliography

• Ahmed, Talat (2018). Mohandas Gandhi: Experiments in Civil Disobedience ISBN 0-7453-3429-6

• Barr, F. Mary (1956). Bapu: Conversations and Correspondence with Mahatma Gandhi (2nd ed.). Bombay: International Book House. OCLC 8372568. (see book article)

• Bondurant, Joan Valérie (1971). Conquest of Violence: the Gandhian philosophy of conflict. University of California Press.

External links

• Gandhi's correspondence with the Indian government 1942–1944

• About Mahatma Gandhi

• Gandhi at Sabarmati Ashram

• Works by Mahatma Gandhi at Project Gutenberg

Popular Posts:

- 1. what lawyer is on fairmount in whitefish bay

- 2. why do whores think that they're worn out pussy is worth more than the best lawyer in town charges

- 3. what kind of lawyer do i need to file a claim on a police officer

- 4. how to contact a lawyer for career shadow

- 5. lawyer who represent nfl concussion steven avery

- 6. how much does a injury lawyer make

- 7. when to hire a lawyer to write a will

- 8. person who needs a lawyer

- 9. how to find a honest lawyer in bay area

- 10. 1985 lawyer who sued baby formula company