See more

May 24, 2019 · Gandhi sailed for England on 4th September, 1888 to study law and become a barrister. He was called to the Bar on 10th June, 1891 and was enrolled in the High Court of England the next day. A day later, he sailed home.

When did Mahatma Gandhi become a lawyer?

Did Gandhi studied law and become a lawyer?

When did Gandhi work as a lawyer in South Africa?

Why was Gandhi allowed to become a lawyer?

Where did Gandhi begin his career as a lawyer?

What was Gandhi's practice?

By the end his practice, his entire practice is devoted to his political, moral, and spiritual beliefs. And at that point he becomes integrated.

Who gave credit to Gandhi?

DiSalvo gives much credit to the many law and history students who read through some 10,000 newspapers from South Africa which held keys to unlocking details of Gandhi’s career as a lawyer and a politician. DiSalvo says it was that Herculean effort that perhaps prevented anyone else from writing this book earlier.

Why did Gandhi withdraw from the case?

“In fact in one of his first cases in India where he tried to launch a practice and failed, he had to basically withdraw from the case because he was too nervous in court!” . DiSalvo remarks.

Where did DiSalvo work?

DiSalvo explains that it was in what was considered at the time a backwater, in South Africa, where he worked to overcome his fear. “And he grew, he rose to the occasion, and he changed. Before he leaves South Africa, before he gives up the practice of law, he’s on his feet giving speeches that last two and more hours.

Who is the leader of Indian nationalism?

Charles R. DiSalvo in his office at the College of Law at West Virginia University. Mahatma Gandhi is widely recognized as a leader of Indian nationalism in British-ruled India who employed nonviolent civil disobedience, inspiring movements for civil rights across the world.

Who is the author of The Man Before the Mahatma?

Author and Woodrow A. Potesta professor of law , Charles R. DiSalvo, recently read excerpts of his new book The Man Before The Mahatma: M.K. Gandhi, Attorney at Law in Morgantown. First published by Random House India, and most recently by University of California Press, DiSalvo says producing this work that explores Gandhi’s early life in South Africa has been a goal since he discovered that Gandhi was in fact a lawyer for 25 years before becoming a pacifist reformer in India.

Who is Mahatma Gandhi?

Gandhi's Life as a Lawyer Revealed. Mahatma Gandhi is widely recognized as a leader of Indian nationalism in British-ruled India who employed nonviolent civil disobedience, inspiring movements for civil rights across the world. A professor at West Virginia University’s College of Law recently published book that explores a side ...

How was Gandhiji a lawyer?

He had the reputation, among both professional colleagues and his clients, of being a very sound lawyer and was held in the highest esteem by the courts. They all recognized his complete integrity and uprightness. 17 Magistrates and judges alike paid careful attention to any case that he advocated realizing that it had intrinsic merits or that he sincerely believed that it had. An expert cross-examiner, he seldom failed to break down a dishonest witness. 18 Gandhiji was, however, equally strict with his own clients. He had been known to retire from a case in open court, and in the middle of the hearing, having realized that his client had deceived him. He made it a practice to inform his client before accepting his brief, that if, at any stage of litigation, he was satisfied that he was being deceived, he would be at liberty to hand back his brief, for, as an officer of the Court, he could not knowingly deceive it. 19 During his professional work it was Gandhiji's habit never to conceal his ignorance from his clients or his colleagues. Wherever he felt himself at sea, he would advise his client to consult some other counsel, or if he preferred to stick to Gandhiji, he would ask his client to let him seek the assistance of senior counsel. This frankness earned Gandhiji the unbounded affection and trust of his clients who were always willing to pay the fee whenever consultation with senior counsel was necessary. 20

Which case enabled Gandhiji to realize early in his career the paramount importance of facts?

3. It was Dada Abdulla's case which enabled Gandhiji to realize early in his career the paramount importance of facts. As he observes in his autobiography "facts mean truth and once we adhere to truth, the law comes to our aid naturally". 9

How did Gandhiji win the case?

Gandhiji took the keenest interest in the case and threw himself heart, and soul into it. 6 He gained the complete confidence of both the parties and persuaded them to submit the suit to an arbitrator of their choice instead of continuing with expensive, prolonged, and bitter litigation. The arbitrator ruled in Dada Abdulla Sheth's favour, and awarded him £ 37,000/- and costs. It was however impossible for Tyeb Sheth to pay down the whole of the awarded amount. Gandhiji then managed to persuade Dada Abdulla to let Tyeb Sheth pay him the money in moderate instalments spread over a long period of years, rather than ruin him by insisting on an immediate settlement. 7 Gandhiji was overjoyed at the success of his first case in South Africa and concluded that the whole duty of an advocate was not to exploit legal and adversary advantages but to promote compromise and reconciliation. 8

What did Gandhi do in South Africa?

1. Mahatma Gandhi sailed for England on 4th September, 1888 to study law and become a barrister. He kept terms at the Inner Temple and after nine months' intensive study he took all his subjects in one examination which he passed. He was called to the Bar on 10th June, 1891 and was enrolled in the High Court of England the next day. A day later, he sailed home. After his return to India he started practice as a lawyer at first in the High Court at Bombay and a little later in Rajkot but did not make much headway in the profession. It was only when the hand of destiny guided his steps to South Africa that he soon made his mark there as a lawyer and as a public worker. Gandhiji practised as a lawyer for over twenty years before he gave up the practice of the profession in order to devote all his time and energy to public service. The valuable experience and skill that he acquired in the course of his large and lucrative practice stood him in good stead in fighting his battles with the South African and British governments for securing political, economic and social justice for his fellow-countrymen. Gandhiji was not a visionary but a practical idealist. As Sir Stafford Cripps has remarked: "He was no simple mystic; combined with his religious outlook was his lawyer-trained mind, quick and apt in reasoning. He was a formidable opponent in argument." 1

Why has the trial of Gandhiji been universally acknowledged to be a great historic trial out-shadowing all

Why has the trial of Gandhiji been universally acknowledged to be a great historic trial out-shadowing all similar trials of leaders and patriots? Surely, not merely because of the personality of the accused, nor because of his extra-ordinary sway over India's teeming millions whom he treated as his own, nor because of its consequences on the political future of India. There is no doubt that these were all contributory factors which invested the trial with a historic significance. However the chief and most important factor which made the trial historic was the profound issue involved in it, namely, that of obedience to law as against obedience to moral duty. It was that issue which elevated the trial to the highest plane and the characters too who played their part in it. The issue raised by Gandhiji in the trial was not an isolated, sporadic issue arising from the breach of Section 124A of the Penal Code though it apparently was made to appear so. It was the perennial issue of Law versus Conscience, an issue of abiding interest to all civilized people of all times. It invoked the inalienable moral right and duty to resist a system of governance whose only claim to loyalty and obedience was superior physical might. The trial is of profound and momentous significance in that Gandhiji during the trial sought to establish beyond doubt the superiority of soul force over sheer brute force, born out of the gospel of self-suffering and the doctrine of willful yet holy withdrawal from all that is foul, base and unholy in human behaviour, a conclusion which will have an abiding purpose and a meaning until humanity survives. 39

Where did Gandhiji stay?

Gandhiji went to South Africa in April 1893 and stayed for a whole year in Pretoria in connection with the case of Sheth Dada Abdulla who was involved in a civil suit with his near relative Sheth Tyeb Haji Khan Mahammad who also stayed in Pretoria.

When was Gandhiji disbarred?

Appendix VII contains the order issued by the Benchers of Inner Temple on 10th November 1922 disbarring Gandhiji and removing his name from the roll of barristers on his conviction and sentence to six years' imprisonment on 18th March 1922 by the Court of the Sessions Judge, Ahmedabad.

Who advised Gandhi to study law?

Mavji Dave Joshiji, a Brahmin priest and family friend, advised Gandhi and his family that he should consider law studies in London. In July 1888, his wife Kasturba gave birth to their first surviving son, Harilal. His mother was not comfortable about Gandhi leaving his wife and family, and going so far from home.

What did Gandhi do in 1921?

Assuming leadership of the Indian National Congress in 1921, Gandhi led nationwide campaigns for easing poverty, expanding women's rights, building religious and ethnic amity, ending untouchability, and above all for achieving swaraj or self-rule.

Why did Gandhi resign from Congress?

He did not disagree with the party's position but felt that if he resigned, his popularity with Indians would cease to stifle the party's membership, which actually varied, including communists, socialists, trade unionists, students, religious conservatives, and those with pro-business convictions, and that these various voices would get a chance to make themselves heard. Gandhi also wanted to avoid being a target for Raj propaganda by leading a party that had temporarily accepted political accommodation with the Raj.

How did Gandhi change his mind?

This changed, however, after he was discriminated against and bullied, such as by being thrown out of a train coach because of his skin colour by a white train official. After several such incidents with Whites in South Africa, Gandhi's thinking and focus changed, and he felt he must resist this and fight for rights. He entered politics by forming the Natal Indian Congress. According to Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed, Gandhi's views on racism are contentious, and in some cases, distressing to those who admire him. Gandhi suffered persecution from the beginning in South Africa. Like with other coloured people, white officials denied him his rights, and the press and those in the streets bullied and called him a "parasite", "semi-barbarous", "canker", "squalid coolie", "yellow man", and other epithets. People would spit on him as an expression of racial hate.

What did Gandhi do to the common Indians?

Bringing anti-colonial nationalism to the common Indians, Gandhi led them in challenging the British-imposed salt tax with the 400 km (250 mi) Dandi Salt March in 1930 and in calling for the British to quit India in 1942. He was imprisoned many times and for many years in both South Africa and India.

Why did Gandhi raise Indian volunteers?

Gandhi raised eleven hundred Indian volunteers, to support British combat troops against the Boers.

How did Gandhi influence his life?

Gandhi's time in London was influenced by the vow he had made to his mother. He tried to adopt "English" customs, including taking dancing lessons. However, he did not appreciate the bland vegetarian food offered by his landlady and was frequently hungry until he found one of London's few vegetarian restaurants. Influenced by Henry Salt's writing, he joined the London Vegetarian Society and was elected to its executive committee under the aegis of its president and benefactor Arnold Hills. An achievement while on the committee was the establishment of a Bayswater chapter. Some of the vegetarians he met were members of the Theosophical Society, which had been founded in 1875 to further universal brotherhood, and which was devoted to the study of Buddhist and Hindu literature. They encouraged Gandhi to join them in reading the Bhagavad Gita both in translation as well as in the original.

Where did Gandhi work after completing his studies?

After completing his studies, Gandhi returns to India to start a law practice in Bombay. However, too shy to speak up in court, Gandhi's attempts to be a lawyer fail and he accepts various other jobs in legal firms. April 1893. Gandhi goes to South Africa to work for a Muslim Indian law firm.

Where did Gandhi study?

Gandhi begins studies at University College London. He studies Indian law and also joins the Vegetarian Society while there. Gandhi avoids eating meat or drinking alcohol throughout his life.

How old was Gandhi when he married Kasturbai?

Gandhi marries Kasturbai Makhanji in an arranged marriage. At the age of 13, Gandhi marries 14 year-old Kasturbai Makhanji. Following the customs of their region, the children are part of an arranged marriage.

What was Gandhi's pamphlet about?

1896. Gandhi publishes "The Green Pamphlet.". Gandhi writes a pamphlet about the discrimination Indians face in South Africa. Great Britain, which controls South Africa, believes that "The Green Pamphlet" is an anti-government document and begins to view Gandhi as a troublemaker. December 1896.

Why is Gandhi called Mahatma?

The title means "Great Soul" and is given by Hindus to only the holiest men. Gandhi is not fond of it because he believes all souls are equal.

Why did Gandhi go to South Africa?

Gandhi goes to South Africa to work for a Muslim Indian law firm. Gandhi agrees to travel to South Africa to help a Muslim Indian law firm with a lawsuit. He is shocked by the racial discrimination he finds there when he learns he is not allowed to travel in the first class section of the train.

What was Gandhi's major turning point?

The trip becomes a major turning point for him as he devotes his life to the pursuit of equality and justice. Spring 1894. Gandhi decides to stay in South Africa. The day he is due to return to India, Gandhi learns about a bill that would deny Indians the right to vote.

Where did Gandhi practice law?

Upon returning to India in mid-1891, he set up a law practice in Bombay, but met with little success. He soon accepted a position with an Indian firm that sent him to its office in South Africa. Along with his wife, Kasturbai, and their children, Gandhi remained in South Africa for nearly 20 years.

Why was Gandhi imprisoned?

Known for his ascetic lifestyle–he often dressed only in a loincloth and shawl–and devout Hindu faith, Gandhi was imprisoned several times during his pursuit of non-cooperation, and undertook a number of hunger strikes to protest the oppression of India’s poorest classes, among other injustices.

What happened to Gandhi in 1948?

In January 1948, Gandhi carried out yet another fast , this time to bring about peace in the city of Delhi. On January 30, 12 days after that fast ended, Gandhi was on his way to an evening prayer meeting in Delhi when he was shot to death by Nathuram Godse, a Hindu fanatic enraged by Mahatma’s efforts to negotiate with Jinnah and other Muslims. The next day, roughly 1 million people followed the procession as Gandhi’s body was carried in state through the streets of the city and cremated on the banks of the holy Jumna River.

Why did Gandhi retire?

In 1934, Gandhi announced his retirement from politics in, as well as his resignation from the Congress Party, in order to concentrate his efforts on working within rural communities.

Why did Gandhi leave South Africa?

In July 1914, Gandhi left South Africa to return to India. He supported the British war effort in World War I but remained critical of colonial authorities for measures he felt were unjust. In 1919, Gandhi launched an organized campaign of passive resistance in response to Parliament’s passage of the Rowlatt Acts, which gave colonial authorities emergency powers to suppress subversive activities. He backed off after violence broke out–including the massacre by British-led soldiers of some 400 Indians attending a meeting at Amritsar–but only temporarily, and by 1920 he was the most visible figure in the movement for Indian independence.

What did Gandhi demand from the British?

Drawn back into the political fray by the outbreak of World War II, Gandhi again took control of the INC, demanding a British withdrawal from India in return for Indian cooperation with the war effort. Instead, British forces imprisoned the entire Congress leadership, bringing Anglo-Indian relations to a new low point.

Why did Gandhi oppose partition?

Gandhi strongly opposed Partition, but he agreed to it in hopes that after independence Hindus and Muslims could achieve peace internally. Amid the massive riots that followed Partition, Gandhi urged Hindus and Muslims to live peacefully together, and undertook a hunger strike until riots in Calcutta ceased.

Who was Gandhi's father?

The name of Gandhi’s father was Karamchand Gandhi. He was the Dewan of the state of Porabandar, which was ruled by a Rana. Karamchand had no much education in the formal sense, but he was able, honest and dutiful as a Dewan. As a man, Karamchand Gandhi was courageous, virtuous and truthful. Gandhi’s mother was Putli Bai. She was extremely religious. Her innocence, goodness and saintly qualities left a permanent influence only her son.

What did Gandhi do during the First World War?

Gandhi returned while the First World War was going only. For one year he observed Indian politics.Gokhale’s death that year made him extremely sorry. As Gandhi began to see India, the poverty of the people moved him deeply. At Champaran in Bihar he took up the cause of the poor peasants and fought only their behalf. At Ahmadabad he fought for the cause of the poor textile workers. At Gujarat, he stood by the side of starving peasants and fought for their relief from tax.

Why did Gandhi support the British government?

While fighting for the poor peasants and workers, Gandhi nevertheless supported the British Government in its war efforts. The Empire was in grave danger. Gandhi thought it a moral duty to stand by the British in their darkest hour of need. He asked the people to help the Government and told the Government about India’s hope ‘of a better future.’

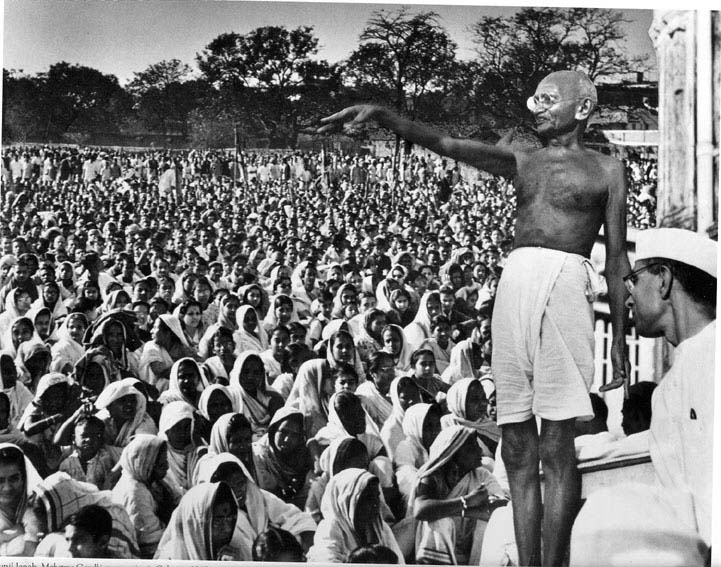

What was Gandhi's first public speech?

Gandhi called a meeting of the Indian community at a place called Pretoria. He addressed them. That was his first public speech in life. His moral force was his only strength. He stood to uphold the dignity of man. He had no fear in him. And, he had no hatred towards the white Government against which he stood. He only demanded justice for his fellowmen. Gandhi’s political life began.

Why did Gandhi go to England?

At that time, some of his well-wishers advised him to go to England to study law and return as a barrister. The idea was attractive. With much difficulty, money was arranged by loan. Gandhi’s mother however, did not like to send her son to that impure land.

Where did Gandhi land?

Gandhi landed at Port Natal or Durban in South Africa. South Africa was a British colony. The number of Englishmen there was very small. But they ruled supreme over the Africans. More than that, the White English men regarded the black Africans and the brown Indians as inferior human beings. India traders, merchants, businessmen and laborers were there in large number. The white people called them all as ‘coolies’ and showered contempt only them. Shortly after his arrival, Gandhi was travelling one evening in train in first class. A white man entered into it and was angry to see a ‘colored’ man there. Poor Gandhi was forced out of the compartment into the platform. There in that cold winter night, sitting in a railway platform of an unfortunate country, Gandhi thought over the vices of white racialism. His mind revolted. He suffered a few more severe insults in the hands of white men including sever blows. But, then, he stood up to challenge, to oppose and resist. The man in Gandhi was roused. He stood to fight against injustice, no matter where and in what conditions.

What was the Gandhian Satyagraha?

It was a new revolution in history. An unarmed people struggled with a powerful Government without fear. Gandhi named it as Passive Resistance or Civil Resistance. But still more appropriately, he called it the Satyagraha. It rested on Truth. It was non-violent. It upheld what was just and right for human dignity. Those who joined the resistance were required to suffer any punishment from Government. They were taught to be fearless but non-violent. The Gandhian Satyagraha proved itself a unique method of revolution. Far away in South Africa, the ignorant, poor and uneducated Indians who had gone there as laborers and were called ‘coolies’ fought bravely against a deposit white Government.

Where did Gandhi go to school?

Where was Gandhi educated? He received his primary education in the city of Porbandar. Being a famous and influential person, some people assume Gandhi was among the brightest students in his school. Contrary to this, Gandhi was an average student. He was not very good at academics or in any sporting activities, however, he grasped some of the most important aspects of his education including good morals. He was also a shy and timid student. The school he went to was a school consisting of boys only and was located on the Western Coast of India.

How old was Gandhi when he went to Alfred High School?

He joined Alfred High School, an all-boys school, at the age of 11 years . There was a lot of improvement in his performance in high school compared to elementary school. The young Gandhi who was not good at anything could now be recognized as a good student in various subjects including English.

What is Mahatma Gandhi's most famous achievement?

He was raised in a middle-class family and was not so exemplary in school especially in elementary school. Gandhi managed to learn and respect the moral principles as well as character training that he got from school.

What was Gandhi's education like?

Gandhi's education was met with challenges right from elementary school up to college. Despite these challenges, he managed to accomplish his goals and inspire many people around the world. Here is a brief overview of Mahatma Gandhi's life during his school years.

Why was Alfred High School renamed after Gandhi?

Alfred High School was later renamed after Gandhi after India's independence. In 2017, the school was closed and converted to a museum.

Who is the most famous person in the history of India?

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi who is famously known as Mahatma Gandhi was more than just a lawyer. He is remembered as an anti-colonial nationalist as he was the leader in India's independence movement. His non-violent tactics became famous around the world and influenced some freedom fighters around the world including Martin Luther King.

Did Gandhi go back to college?

After some time, Gandhi decided to go back to college. He opted to take a different course, Law. Since he had studied in India all his life, he decided to make a change and study in England. His decision was met with many challenges starting from his own family. His mother was not supportive of him leaving India and the local chiefs excommunicated him. To put his family and other people who thought he would be influenced to go against his religion, he made a vow not to eat meat, drink alcohol or get involved with other women.

What did Gandhi do when his contract expired?

When his contract expired, he spontaneously decided to remain in South Africa and launch a campaign against legislation that would deprive Indians of the right to vote. He formed the Natal Indian Congress and drew international attention to the plight of Indians in South Africa. In 1906, the Transvaal government sought to further restrict the rights of Indians, and Gandhi organized his first campaign of satyagraha, or mass civil disobedience. After seven years of protest, he negotiated a compromise agreement with the South African government.

Who killed Gandhi in 1948?

On January 30, 1948, he was on one such prayer vigil in New Delhi when he was fatally shot by Nathuram Godse, a Hindu extremist who objected to Gandhi’s tolerance for the Muslims.

What was Gandhi's role in the Indian independence movement?

After World War II, he was a leading figure in the negotiations that led to Indian independence in 1947. Although hailing the granting of Indian independence as the “noblest act of the British nation,” he was distressed by the religious partition of the former Mogul Empire into India and Pakistan. When violence broke out between Hindus and Muslims in India in 1947, he resorted to fasts and visits to the troubled areas in an effort to end India’s religious strife. On January 30, 1948, he was on one such prayer vigil in New Delhi when he was fatally shot by Nathuram Godse, a Hindu extremist who objected to Gandhi’s tolerance for the Muslims.

What was Gandhi's first act of civil disobedience?

Gandhi’s first act of civil disobedience. In an event that would have dramatic repercussions for the people of India, Mohandas K . Gandhi, a young Indian lawyer working in South Africa, refuses to comply with racial segregation rules on a South African train and is forcibly ejected at Pietermaritzburg. Born in India and educated in England, Gandhi ...

What was Gandhi's first campaign?

In 1906, the Transvaal government sought to further restrict the rights of Indians, and Gandhi organized his first campaign of satyagraha, or mass civil disobedience. After seven years of protest, he negotiated a compromise agreement with the South African government.

Why did Gandhi travel to South Africa?

Settling in Natal, he was subjected to racism and South African laws that restricted the rights of Indian laborers. Gandhi later recalled one such incident, in which he was removed from a first-class railway compartment ...

What did Gandhi think of his life in the law?

There are no reports indicating just what Gandhi thought at this time of what a life in the law meant , if he gave any thought to it at all. Indeed, there are no reports indicating any resistance on Gandhi's part to the idea of training in the law, except his timid inquiry whether he could be sent to study his first love, medicine, instead of law, a proposal which was quickly discarded in the wake of his brother's declaration that it was their father's wish that Mohandas become a lawyer, not a physician. Thus it appears that Gandhi accepted the choice of profession made for him with little more objection than that he voiced to the choice of a wife his family made for him.

What was Gandhi's choice of career?

The choice of career, like the choice of marriage, was not Gandhi's to make. Just as his marriage at age thirteen to Kasturba was arranged for him, so, too, was the decision to study law the product of family forces other than his own will. Gandhi's father, Karamchand Gandhi, had met with some success in ascending to positions of high bureaucratic power, serving as prime minister of the small dominions of Porbandar, Rajkot, and Vankaner. While Karamchand's political career failed to make his family wealthy, neither did the family want for the basics of life. Theirs was a day-to-day stability. Karamchand's health, however, worsened as a result of age and accident, and eventually he was forced to give up his career in government. When he passed away, he did not leave the family anything on which to live. None of Gandhi's three older siblings had the prospects required to carry the family. Accordingly, the burden settled on the shoulders of young Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi.

Why did Gandhi delay the Roman law exam?

Gandhi would have completed his first four terms with the end of the Trinity term in mid-June 1889, yet he did not take the Roman law examination until March 1890. Why the delay? The most likely explanation is that Gandhi divided his attention for a substantial period of time between his preparation for the Roman law and London examinations. Whatever the reason for the delay in taking the Roman law examination, Gandhi was not hurt by it. He finished sixth out of the forty-six who sat for it. Not a bad showing for one who was not a "University man."

How did Gandhi travel to London?

Even with his immediate family in the fold, however, Gandhi's plan was controversial. To make his way to London, he needed to travel from Rajkot to Bombay, where he would board a steamer for England. Bombay was even more populated by members of his caste than his hometown. This was unfortunate for Gandhi; there was heated resistance on the part of his caste to the notion of any of their members going abroad. A series of incidents in which Gandhi was peppered with harassment on the streets of Bombay for his intentions was followed by an even more dramatic public confrontation. Gandhi was forced to attend a meeting of his entire caste, at which the subject of his going abroad would be addressed before the whole group. The discussion came to a head with this ultimatum issued by the leader of the caste to Gandhi: "We were your father's friends, and therefore we feel for you; as heads of the caste you know our power. We are positively informed that you will have to eat flesh and drink wine in England; moreover, you have to cross the waters; all this you must know is against our caste rules. Therefore, we command you to reconsider your decision, or else the heaviest punishment will be meted out to you." Gandhi's unequivocal response was to reject the threat, saying that he was going nonetheless. The head of the caste thereupon decreed that Gandhi was no longer his father's son, ordered all members of the caste to have nothing to do with him, and declared him an outcast.

How many years did Gandhi spend in England?

Regardless of the little thought Gandhi himself may have given to studying the law or being a barrister, we do know that he relished the prospect of three years in England. Perhaps this is what motivated him to overcome four serious obstacles to his studying law there: the lack of any means to finance his legal education overseas, the concerns of his wife's family, the uncertainty of his mother, and the opposition of his caste.

Where did Gandhi go to college?

After completing high school, Gandhi passed the Bombay University matriculation examination and took up his studies at Samaldas College in Bhavnagar in 1887. He wasn't much of a student, being both uninterested in and unable to follow his professors' lectures. Compounding the difficulty he had with his studies were his physical problems. Gandhi complained of constant headaches and nosebleeds due, some conjectured, to the hot climate. Gandhi's summer vacation from Samaldas could not come too soon. In late April 1888, at the start of his vacation, Gandhi and his oldest brother, Lakshmidas, decided to visit a friend of the family, the Brahmin Mavji Dave. On hearing Gandhi's complaints about college, including his prediction that he would fail his first-year examination, Mavji suggested that Gandhi be sent to England to study for the bar. This, he thought, would prepare Gandhi to reclaim his father's position and income in much better fashion than would the pursuit of an ordinary college degree. The calculus being made at this time did not involve altruistic concerns. The naked purpose of providing young Gandhi a legal education was to guarantee an income for the family. It is not surprising, then, that when Gandhi was asked in 1891 why he had come to England to study the law, his forthright reply was "ambition."

Who was the British administrator of Porbandar state?

Lakshmidas assumed the task of obtaining financing. His first attempt at securing the necessary funds was to send Gandhi off to beseech Frederick Lely , the British administrator of Porbandar state, for governmental assistance. The Gandhis hoped that their reputation with Lely, established by the late Karamchand, would lead Lely to open the state coffers. After a four-day journey to Porbandar and after elaborately rehearsing his request, Gandhi was startled when his request was dismissed out-of-hand. Lely brusquely advised him to secure his B.A. before attempting the study of law, after which Lely would consider granting some aid. Gandhi then turned to his cousin Parmanandbhai, who promised his financial support, as did Meghjibhai, another cousin. Despite their promises, there is no evidence that either of these cousins aided Gandhi; indeed Meghjibhai is on record as later angrily denying Gandhi any help. Two additional governmental representatives whom Gandhi approached were as unhelpful as Lely. Other than some small amounts of money and a silver chain that some of his friends gave him on his departure from Bombay, it appears that Gandhi received no financial help from any of his friends, extended family, or governmental officials. If Gandhi was to go to London, it would be by exhausting what capital remained with his immediate family after the death of Karamchand.

Overview

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist and political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful campaign for India's independence from British rule, and to later inspire movements for civil rights and freedom across the world. The honorific Mahātmā (Sanskrit: "great-souled", "venerable"), first applied to him in 1914 in South Africa, …

Biography

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on 2 October 1869 into a Gujarati Hindu Modh Bania family in Porbandar (also known as Sudamapuri), a coastal town on the Kathiawar Peninsula and then part of the small princely state of Porbandar in the Kathiawar Agency of the Indian Empire. His father, Karamchand Uttamchand Gandhi (1822–1885), served as the dewan(chief minister) of Porb…

Principles, practices, and beliefs

Gandhi's statements, letters and life have attracted much political and scholarly analysis of his principles, practices and beliefs, including what influenced him. Some writers present him as a paragon of ethical living and pacifism, while others present him as a more complex, contradictory and evolving character influenced by his culture and circumstances.

Literary works

Gandhi was a prolific writer. His signature style was simple, precise, clear and as devoid of artificialities. One of Gandhi's earliest publications, Hind Swaraj, published in Gujarati in 1909, became "the intellectual blueprint" for India's independence movement. The book was translated into English the next year, with a copyright legend that read "No Rights Reserved". For decades he edited …

Legacy and depictions in popular culture

• The word Mahatma, while often mistaken for Gandhi's given name in the West, is taken from the Sanskrit words maha (meaning Great) and atma (meaning Soul). Rabindranath Tagore is said to have accorded the title to Gandhi. In his autobiography, Gandhi nevertheless explains that he never valued the title, and was often pained by it.

See also

• Gandhi cap

• Gandhi Teerth – Gandhi International Research Institute and Museum for Gandhian study, research on Mahatma Gandhi and dialogue

• Inclusive Christianity

• List of civil rights leaders

Bibliography

• Ahmed, Talat (2018). Mohandas Gandhi: Experiments in Civil Disobedience ISBN 0-7453-3429-6

• Barr, F. Mary (1956). Bapu: Conversations and Correspondence with Mahatma Gandhi (2nd ed.). Bombay: International Book House. OCLC 8372568. (see book article)

• Bondurant, Joan Valérie (1971). Conquest of Violence: the Gandhian philosophy of conflict. University of California Press.

External links

• Gandhi's correspondence with the Indian government 1942–1944

• About Mahatma Gandhi

• Gandhi at Sabarmati Ashram

• Works by Mahatma Gandhi at Project Gutenberg

Popular Posts:

- 1. what name to put if theres no name of lawyer during deposition

- 2. finding a divorce lawyer who understands railroad retiremtt

- 3. how to find a dental lawyer for negligence in pa.

- 4. what does an average lawyer cost

- 5. what is it called when you dont pay a lawyer until after

- 6. what to expect with your first meeting with disability lawyer

- 7. letter to lawyer when firing due to not showing up in court

- 8. how much for immigration lawyer marriage fiance

- 9. who were 26 lawyer presidents

- 10. what to buy woman lawyer