Why choose attorney Linda Brown?

Mar 26, 2018 · Linda Brown was the child associated with the lead name in the landmark case Brown v. ... who represented different states. ... The lead attorney working on behalf of the plaintiffs was future ...

What is the significance of Linda Brown's case?

The Law Office of Linda M. Brown has been providing clients in the Baltimore-Washington Metro area with top quality legal representation since 1989. As a General Practice Law Firm, we are dedicated to providing excellent representation that is both efficient and effective. Our knowledgeable and friendly staff understands that every client has a unique set of needs, and …

Who was the lead lawyer for Brown v Brown?

Mar 17, 2020 · Prior to law school, Mrs. Brown served in the United States Navy. During law school, Mrs. Brown received the Veterans Law Institute Award and William F. Blews Pro Bono Service Award for providing legal guidance to the community. Mrs. Brown was also an Equal Justice Works Americorp JD Scholar during her time at Stetson until she graduated and joined …

Who were Linda Brown and Terry Lynn Brown?

May 27, 2021 · Attorney Linda M. Brown. 5.0 stars. Posted by Anthony May 27, 2021. I hired Ms. Brown in 2015 to represent me in my divorce case. Ms. Brown did a outstanding helping me get my kids and save my home. As of today, Ms. Brown still represent me in all my cases. I highly recommend Ms. Brown if you need an excellent attorney.

Who represented Linda Brown in Court?

Who was the lawyer who argued for Linda Brown and who was the chief justice who made the decision about segregation in schools?

Who represented the Brown family?

Who was the naacp attorney in Brown v Board?

Who won Plessy vs Ferguson?

Who was the defendant in Brown v. Board of Education?

Who represented Brown in Brown vs Board of Education?

Who was the first African American to be appointed to the Supreme Court?

What happened after Brown v Board?

Who led the naacp defense team in Virginia?

What were the 5 cases in Brown v. Board of Education?

Welcome to The Law Office of Linda M. Brown!

The Law Office of Linda M. Brown has been providing clients in the Baltimore-Washington Metro area with top quality legal representation since 1989. As a General Practice Law Firm, we are dedicated to providing excellent representation that is both efficient and effective.

About Us

For over 25 years Linda M. Brown has been serving the legal needs of Laurel, Maryland. Her professional, caring approach to the law and her clients is what continually sets her apart.

Associate

Linda Brown received her undergraduate degree from the University of South Florida and law degree from Stetson University College of Law. Prior to law school, Mrs. Brown served in the United States Navy. During law school, Mrs. Brown received the Veterans Law Institute Award and William F.

Bounce Back: Tips to help men navigate family law

All cases cited in this book are Florida cases and should not be considered advice for any other state.

What is Linda Brown's legacy?

Legacy. In addition to her lifelong advocacy in law and education, Linda Brown's legacy includes the declaration of historic landmark status for both Sumner, the nearby whites-only school she sought to attend alongside her neighbors, and Monroe, a more distant, segregated elementary school.

Where did Linda Brown go to school?

Although Linda Brown attended segregated Monroe Elementary, which was more than a mile away from her home, Sumner Elementary was six blocks from her house. After her parents were denied admission to Sumner, they were able to join the NAACP's class action suit.

What was Linda Brown's parents' plan to enroll her in Sumner Elementary School?

At the direction of the NAACP, Linda Brown's parents attempted to enroll her in nearby Sumner elementary school and were denied. This allowed Brown's family to join the group of civil rights lawsuits coordinated and supported by the NAACP, which would ultimately be decided in the US Supreme Court case Brown v.

Why was the Browns name listed first?

The Browns' name was alphabetically first among the families suing the Topeka Board of Education which is why their name was listed first and the case is commonly referred to as Brown vs. the Board of Education.

What was the Brown v Board of Education case about?

At the time of the Brown v. Board of Education case, accommodations for black students in public schools were substandard . Many black children were educated in schools that lacked basic amenities like running water or proper classrooms. As long as black schools and white schools offered the same accommodations, schools could remain segregated under the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision.

Why did the NAACP litigate cases?

In order to force the government to rectify the resource disparities between schools, the NAACP litigated cases around the country in hopes that one case would eventually make it to the Supreme Court. In Topeka, the NAACP found 13 families willing to enroll their children in non segregated schools. Although Linda Brown attended segregated Monroe Elementary, which was more than a mile away from her home, Sumner Elementary was six blocks from her house. After her parents were denied admission to Sumner, they were able to join the NAACP's class action suit

Who was Linda Brown?

Linda Brown, who as a schoolgirl was at the center of the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case that rejected racial segregation in American schools, died in Topeka, Kan., Sunday afternoon. She was 76. Her sister, Cheryl Brown Henderson, confirmed the death to The Topeka Capital-Journal.

Who was at the center of Brown v. Board of Education?

Linda Brown, Who Was At Center Of Brown v. Board Of Education, Dies : The Two-Way As a schoolgirl, she was at the center of the landmark Supreme Court case that rejected racial segregation in American public schools. She died Sunday in Topeka, Kan. She was 76.

What was the Brown v Board of Education case?

Board of Education, involved several families, all trying to dismantle decades of federal education laws that condoned segregated schools for black and white students. But it began with Brown's father Oliver, who tried to enroll her at the Sumner School, an all-white elementary school in Topeka just ...

Why didn't Leola Brown go to school?

She broke it down in simple terms: "It was because her face was black. ... and she just couldn't go to school with the white races at that time."

Which amendment was struck down?

Two years later the court unanimously ruled to strike down the doctrine of "separate but equal." The justices agreed that it denied 14th Amendment guarantees of equal protection under the law.

Who was Linda Brown?

Linda Brown, who as a little girl was at the center of the Brown v. Board of Education case that ended segregation in American schools, has died, a funeral home spokesman said. Brown, 75, died Sunday afternoon in Topeka, Kansas, the spokesman said. Brown was 9 years old in 1951 when her father, Oliver Brown, tried to enroll her at Sumner Elementary ...

What happened to Linda Brown?

Her enrollment in the all-white school was blocked, leading her family to bring a lawsuit against the Topeka Board of Education. Four similar cases were combined with the Brown complaint and presented to the US Supreme Court as Brown v. Board of Education. The court's landmark ruling on the case on May 17, 1954, led to the desegregation of the US education system.

What was the Supreme Court ruling in Plessy v Ferguson?

The court directed schools to desegregate “with all deliberate speed,” but it failed to establish a firm timetable for doing so. The Supreme Court would outline the process of school desegregation in Brown II in 1955, but it would take years for schools across the nation to fully comply.

What was the key piece presented against segregation?

One of the key pieces presented against segregation was psychologist Kenneth Clark's "Doll Test" in the 1940s. Black children were shown two dolls, identical except for color, to determine racial perception and preference. A majority preferred the white doll and associated it with positive characteristics. The court cited Clark's study, saying, "To separate [African-American children] from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone."

What amendment states that no citizen can be denied equal protection under the law?

The court ruled in May 1954 that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” a violation of the 14th Amendment of the US Constitution, which states that no citizen can be denied equal protection under the law.

Where did Linda Brown go to school?

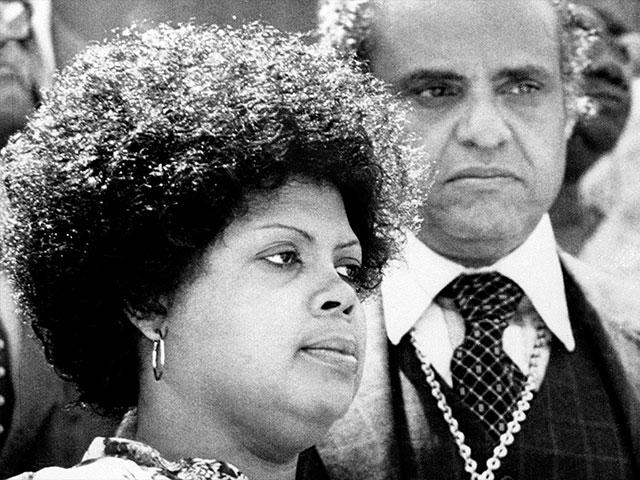

Linda Brown, center, and her sister Terry Lynn, far right, take a bus to Monroe Elementary School, an all-black school in Topeka, in 1953. The Brown sisters attend class at Monroe Elementary School in 1953. Linda is on the front row on the right, and Terry Lynn is in the far left row, third from the front.

Where did the Brown sisters go to school?

The Brown sisters attend class at Monroe Elementary School in 1953. Linda is on the front row on the right, and Terry Lynn is in the far left row, third from the front. Photos: Desegregating US schools. PHOTO: New York World-Telegram/the Sun/Library of Congress.

What was the name of the case that consolidated the Brown v. Board of Education case?

In 1952, the case — Oliver L. Brown et. al v. Board of Education of Topeka — was appealed to the Supreme Court, which consolidated the case with other school desegregation cases from across the country. The court combined five cases from Delaware, Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia and Washington, D.C., into a single case, which became known as Brown v. Board of Education.

Why was Linda Brown not allowed to attend school?

Brown. March 27, 2018. Share. In September 1950, a black father took his 7-year-old daughter by the hand and walked briskly for four blocks to an all-white school in their Topeka, Kan., neighborhood. Sumner was the closest elementary school to their home, but Linda Brown was not allowed to attend because of the color of her skin.

Why did Oliver Brown go to the principal's office?

Inside Sumner School, Oliver Brown told his little girl to take a seat in the foyer, while he went into the principal’s office to demand equality for his child. Linda Brown could hear the voices inside the principal’s office getting louder. Advertisement.

Why did Oliver Brown tell his little girl to take a seat in the foyer?

Inside Sumner School, Oliver Brown told his little girl to take a seat in the foyer, while he went into the principal’s office to demand equality for his child.

What was the landmark decision that ended decades of segregation in schools?

He did not know that what he and his daughter were about to do would change history, leading to the landmark Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board of Education, that would end decades of public school segregation.

When did the Topeka integration happen?

In Topeka, Linda Brown recalled, integration went smoothly in the fall of 1954.

Who tried to enroll their children in all white Topeka schools?

Oliver Brown and other black parents who tried to enroll their children in all-white Topeka schools were met with flat-out refusals.

Popular Posts:

- 1. mr. smith, who is a well-respected lawyer, has just retired from active practice.

- 2. how much is an immigration lawyer cost

- 3. parole lawyer can not talk to the inmates why not?

- 4. international lawyer does what

- 5. who is hogans lawyer against gawker

- 6. i have my fathers will but need to find out who the lawyer is who wrote it

- 7. what other jobs can a lawyer do

- 8. what type of college education is needed to be a lawyer

- 9. how to teport a lawyer for misconduct in california

- 10. hillary lawyer in texas who take the cases of illegal immigrants